The day Talky and Jitsi failed – and why end-to-end monitoring is critical

It was a bad day for me. 14 January 2016.

I had a demo to show to a customer of testRTC. Up until that point, the demos we’ve shown potential customers were focused on Jitsi or Talky (depending on who did the demo).

There were a couple of reasons for picking these services for our demos:

- They are freely available, so using them required no approval from anyone

- They require no login to use, so the script on top of them was a simple one to explain and showcase

- They support video, making them visual – a good thing in a demo

- They support more than two participants, which shows how we can scale nicely

- In the case of Jitsi, you can visually see if the session is relayed or not – making it easy to show how our network configuration affects WebRTC media routing

We used to use them a lot. For me, they were always stable.

Until 14th of January last month, when both mysteriously failed on me. The failure was a subtle one. The site works. You can join sessions. You can see your camera capture. It tells you it is waiting for other participants to join. But it does that also when someone joins – that other participant? He sees the same message exactly.

You have two or more people in the same session, all waiting for each other, when they are already all effectively “in the meeting”.

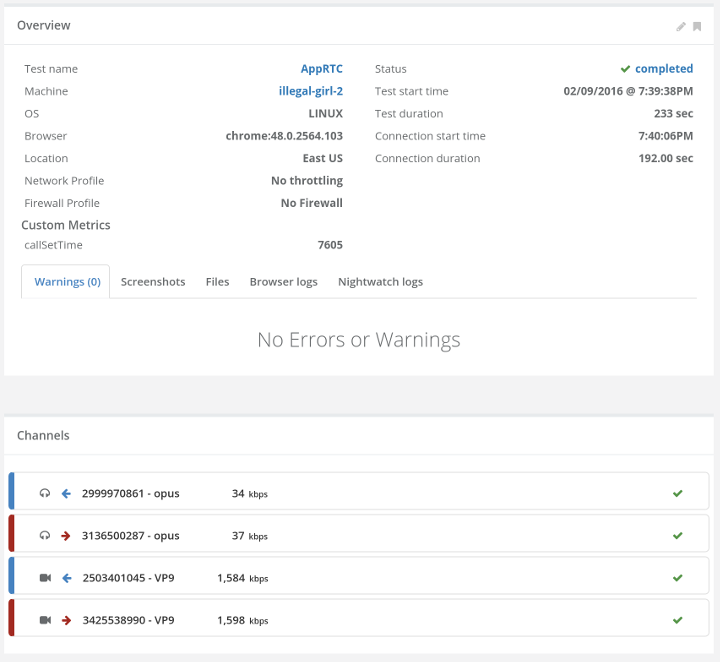

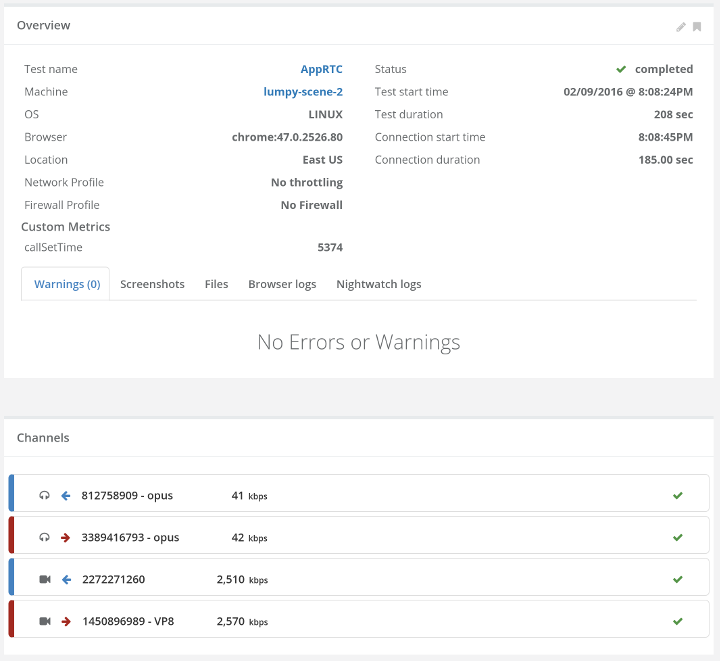

Our scheduled demos for the day failed. We couldn’t show a decent thing to customers – relying on a third party was a small mistake – we switch to show demo on other services – but it cost us time in these meetings. Since then, we’ve gone AppRTC for our baseline.

–

I don’t know why Jitsi and Talky failed on the same day. They both make use of the Jitsi Videobridge, but I don’t believe it was related to the videobridge or even to the same issue – just a matter of coincidence.

While these things happen to all of us, we need to strive for continuous improvement – both in the time it takes us to find an issue as well as fixing it.